Erschienen in: Zeitschrift für Inklusion, Ausgabe 01/2009 Zeitschrift für Inklusion (01/2009)

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- The sixties and the principle of rehabilitation

- The seventies: Part-time special education and integration

- The eighties: change in special education categorization

- The nineties: medicalization of special education

- Present time: rapid growth of segregated education

- Reasons for the growth of special education

- Recent discussion on inclusion

- References

The idea of integration, or the principle of the primacy of mainstream class placement in the education of students with special needs, was first expressed in Finland in the report of the Rehabilitation Committee in 1966. The date was not a coincidence: in its significance the late sixties were, in many ways, an exceptional point in time. In the parliamentary election of 1966 the left wing parties achieved a majority in the parliament. This political change coincided with a turning point in Finnish society as a whole. The process of modernization and urbanization had led to the point where the economic structure of the country was shifting that of an industrial to a post-industrial phase. The shift was manifested in the numbers of people working in the service sector, which superseded the numbers of those working in industry. The concomitant cultural change was expressed in the upheaval of societal values seen in many "cultural wars" of the time.

The construction of a welfare society meant the widening of public services. A widening professional sector sought new customer groups as clients. One of these groups was people with intellectual and mental disabilities who, until that time, were mainly treated in institutions. The ideas of "rehabilitation" launched during the fifties by the International Labour Organization (ILO) now found breeding ground in Finnish society. The change in ideology was revolutionary, and was also noticed by the contemporaries. For example, the Rehabilitation Committee characterized the ideological change as expressing "a new conception of civil rights and human value" (Rehabilitation committee, 1966, 9).

The structure of special education at this time contained two types of special classes: auxiliary classes for students with learning difficulties and other separate classes for students with emotional and behavioural problems. Additionally, there were a few state schools mainly for students with sensory disabilities. The number of students in special classes remained under two percent.

During the educational reform which took place from 1972-1977 the previous dual educational system was superseded by a unified and obligatory nine year comprehensive school, called "peruskoulu", for all children. School began at the age of seven and continued until an age 16. After completion of comprehensive school the voluntary school path continued either in vocational education or in a three year upper secondary high school.

Special education achieved great attention in this reform. The special education division was founded in the National Board of Education and two committee reports were published on the organisation of special education in Finland. The forms of traditional special education were secured but, additionally, the principle of integration was launched. On one side the new concept expressed positive content of the occurring paradigm shift from institutional care to rehabilitation. On the other side it very early expressed its ideological nature as a concept that helped to legitimate the exclusion of disabled people. Integration was considered conditional and depended on the "readiness" of the person.

A new profession of special education teachers, professionals without a grade level class responsibility, was established. In this so called "part-time special education" students received individual or group-based support without formal enrolment into special student status. This led to a conflict with the professional union of teachers, OAJ, which declared a lock-out for those positions in the schools which offered them. As a compromise it was at last agreed that the new profession was not allowed to influence reductions in the number of relocations into special classes (Kivirauma, 1989). This it surely did not bring about, as the main focus of part-time special education for a long time was to address the phonetic difficulties of students such as the correction of pronunciation for difficult Finnish sounds. The number of special class students in the seventies had increased to about two percent of the overall student population in comprehensive schools (Statistics Finland, 1981).

From 1983 onwards, a new law concerning comprehensive schools changed the field of special education. The two older forms of special education classes, the auxiliary school (Hilfschule) for students with learning difficulties and the "observation classes" for students with emotional and behavioural problems were now superseded by a system which could be characterised as principally a non-categorical system of special education. Local municipalities were now allowed to categorize their special education classes as they wanted, though most of the older terms still survived.

There was not, however, a true change from categorical to non-categorical special education. First, strong categorical features came from state funding, which portioned out state support on an individual basis in accordance with the level of disability. Second, local municipalities began to develop new, more medical, special education categories. Third, the special teacher education programs continued to use categorical labels such as "special teacher for the maladjusted", "adapted education" or "training school education". Training school education referred to students with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities which were now at last entitled to enter comprehensive school. During the eighties the proportion of special class students in comprehensive schools grew approximately from two to three percent (Statistics Finland, 1989).

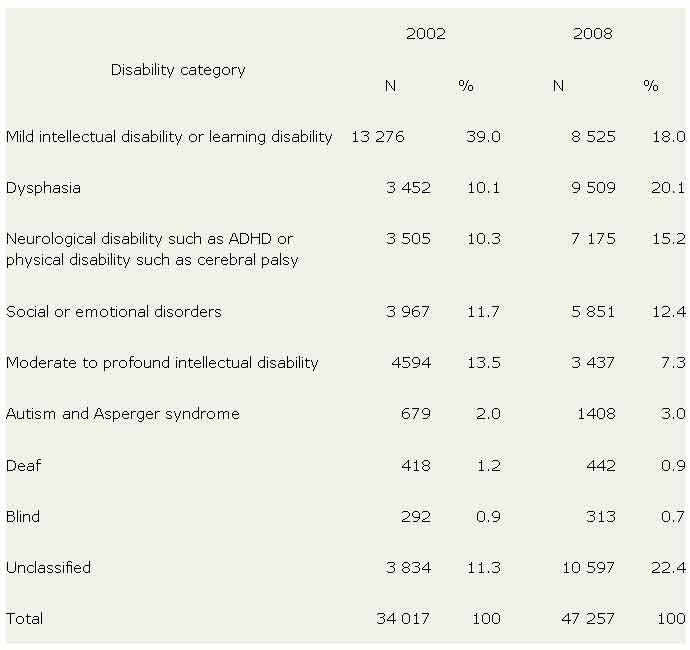

One consequence of the liberation from special class categories was the sudden emergence of new types of special needs categories. The popularity of these categories began to fluctuate rapidly as can be seen from Table 1. For example, the proportion of students with dysphasia increased from 10% to 20% in just six years.

Table 1: Reason for enrollment in special education (Statistics Finland: Education 2003 and 2009)

An important characteristic of these new popular categories was their medical nature. New diagnoses such as "dysphasia", "autism", and "ADHD" attained popularity at the expense of older categories such as mental retardation. A common feature of the new popular diagnoses was their obscurity. Instead of a clear-cut collection of symptoms they resembled more vague metaphors. This medical turn can be seen as the late fruit of the rehabilitation paradigm which was adopted twenty years earlier. The new categorizations were more merciful as compared to the older ones because children were no longer seen as "bad" or "stupid" but as "sick" and in need of rehabilitation (Conrad & Schneider, 1980/1992). This change in perception from "badness" to "sickness" also helped to give new legitimacy to special education. The proportion of comprehensive school students transferred into special classes now grew up to four percent (Table 2). Students with severe and profound intellectual disabilities were now also accepted into comprehensive school in 1997 as the final small disability group thus far marginalized to the outside.

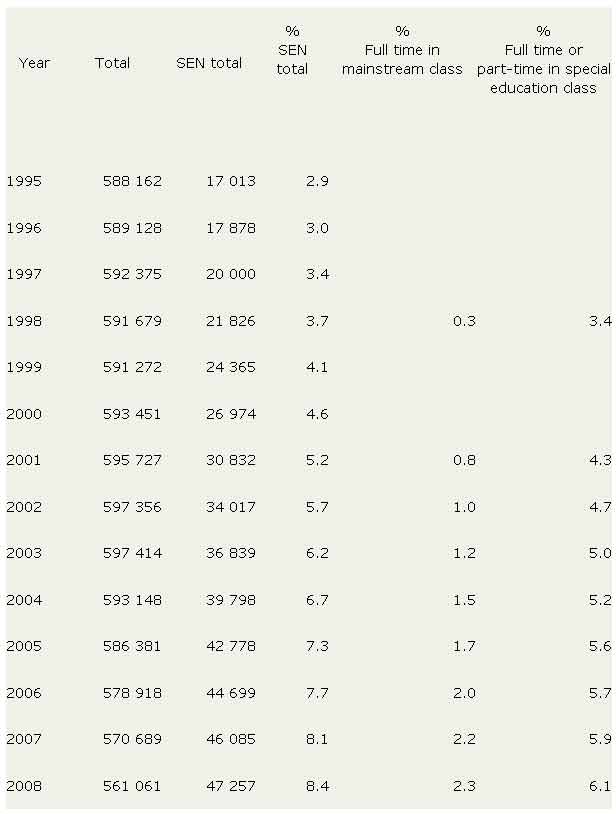

The last ten years have witnessed a rapid growth of segregated special education in Finland (Table 2).

Table 1: Number of students in comprehensive school in Finland, and the number and placement of students with special educational needs (SEN) in various environments (Statistics Finland: Education 1999 - 2009)

Now the proportion of students in special schools and special classes has increased to over six percent, maybe the highest percentage reported anywhere in the world at the present time. Other supports, such as the increasing use of part-time special education have not been effective in reducing this development. During the school term of 2006-2007 of the students in comprehensive schools, 22.2% received part-time special education (Statistics Finland, 2009). In addition, the number of integrated students has also grown. This was due to a change in funding legislation in 1998, which also guaranteed additional state support for those special education students not removed into special classes.

The relative proportion of students in special schools was 2.0% in 1998 and 1.4% in 2007. The slight fall in special school placements seems to be mainly technical: many special schools have been administratively united to mainstream schools. The number of special schools has dropped to about 160. Most of them probably were schools for students with mild disabilities (former auxiliary schools).

Large towns slightly more often use special class placements than rural schools. While in 2005 a total of 5.6% of students were moved in special classes in the country as a whole, the average proportion in larger towns was at a higher percentage, 6 - 9%. Large towns also relied more on separate special schools (Memo, 2006). In contrast, in sparsely inhabited areas, such as Lapland, special class placements have remained rarer than elsewhere. The least number of placements are in the Swedish speaking part of Finland. This may indicate a cultural influence from Sweden where special class placements are much rarer than in Finland. The significant distances in the countryside of Finland explain why integration is more common in rural areas.

Finland differs in the amount of segregated education from its Nordic neighbours Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, where the proportion of segregated education is very low. According to statistics collected by the European Agency of Special Education (2003), Finnish numbers are more comparable with the situation in Germany, Switzerland, and Belgium.

A simple explanation for the large percentage of segregated education is the models of financing. In Finland local authorities receive extra money for each student removed into special education. It has been shown that this kind of financing explains best the international differences in the number of students in special education (Meijer, J.W., 1999). The second reason is linked with teacher professionalism. If a teacher can have a difficult student from her class removed, she can secure for herself a less stressful future in her work. Finnish teachers have got a strong union, and it has taken a very negative stance towards educational integration (OAJ, 1989). Teachers, like all other professional groups, have step by step achieved more power in the affairs of local municipalities at the cost of local political process (Heuru, 2000). This has given teachers more influence in guiding schools in the directions they want schools to go.

The third reason for the large proportion of segregated education lies in the Finnish set of values. In Finland, the shift from an agricultural to an industrial society occurred internationally quite late, during the late forties. The industrial phase remained brief, and the new post-industrial society began to emerge during the late sixties. This means that the traditional values of agricultural and industrial societies still prevail in Finland to a greater extent than in many other countries. These traditional values stress overall conformity and tend to reject people who are considered socially deviant. The Finnish traditional set of values also manifests itself in the internationally high proportions of past sterilization of people with disabilities, high proportion of disabled people in institutions, or in the exceptionally high frequency of fetal screening (Emerson, et. al., 1996; Meskus, 2003).

Traditional Finnish sets of values combined with strong teacher professionalism together explain the high legitimacy of segregated special education in Finnish society. The increasing numbers of students in special education are interpreted by representatives of the government as a healthy answer to increasing pathological conditions of children. The international discussion on inclusion (UN, 1993; Unesco, 1994) was first met in Finland by silence, which continued for several years (e.g. Blom, et al., 1996). At the political level, inclusion is not raised as a goal to be sought. Instead, it is understood as a state that has already been achieved, because all that is possible has already been done. The main focus of special education policy is localized in the neoliberal philosophy of "early intervention", where problems are found in the pathological conditions of individual children (Plan for Education and Research 2007-2011 by the Ministry of Education). This focus is evident also in the Special Education Strategy report of the Special Education Committee of the Ministry of Education (2007). Furthermore, none of the political parties have raised the issue of inclusive education, outside of the small left wing party, The Left Alliance.

Integration, or inclusion, is commonly conceived of as an already achieved and established state of affairs. Since the rehabilitation committee of 1966, the official documents of the National Board of Education have repeatedly stated that integration is a primary choice which, however, is not always possible to achieve. What is "possible" depends on the abilities of the person himself, and these limits are decided by teachers. A popular scapegoat for the lack of integration is found in deficits in teacher education (Special Education Committee, 2007). According to this explanation integration is not possible because teachers have not acquired the necessary skills in their education. Antagonists of this explanation underline that current teacher education is fully adequate in this respect and gives readiness for all teachers to include students with disabilities.

The academic world of special education has traditionally taken a conservative stance towards inclusion. Popular arguments for special education have stressed that "place is not important" or "more research is needed" before inclusion can be activated (Blom et al, 1996). Plausible popular legitimisation of special classes has been created through circular arguments: a child is, of course, in need of special education if she has special educational needs.

Very recently there has been observable some change in the discussion. First, some large disability organizations, e.g. the Parents' Association for People with Intellectual Disabilities, The National Council on Disability, and the Finnish Association on People with Physical Disabilities have presented critical statements, not heard previously, on current policy which favours increased placement of students in special classes. These organizations have begun to refer to international goal statements on inclusive education, like the Salamanca statement. Second, the academic field of special education has begun to experience some polarization in the question of inclusion, and more positive sounds are being heard in favour of inclusion. This argument is observed, for example, in a recent addition on special education of the Finnish educational journal "Kasvatus" (2/2009). Additionally, a current textbook written by leading special education professors (2009) refers to inclusive education in a cautiously positive tone of voice, even if traditional special education is in no way criticized. It also gives space to the presentation of the international inclusion movement and international statements.

The above mentioned events are weak signals which probably foreshadow the slow change of societal values underway in the direction of greater tolerance towards people with disabilities. More radical changes could be expected from a different direction. The preparation of new legislation concerning the state funding of local municipalities is currently taking place. Preliminary, unofficial information on the new principles concerning state support give some promise for the demolition of the present individual-based funding model of special education in favour of a more global solution. If the change happens it, in all probability, will mean a free fall in the number of special class placements. Inclusive development may thus become materialized as an unintended consequence of a bureaucratic funding reform.

Currently, Finland is a black sheep in the international movement on inclusive education. The legitimacy of separate special education is strong and unquestioned. Since the mainstream in most other countries is towards inclusive education, the situation of Finnish school authorities is not always comfortable. There is a continuous threat of a legitimacy crisis in special education. Until now the threat has been successfully handled first through the means of ignoring the international discussions, statements and policies, and lately by changing the meaning of the concept of inclusion. Instead of inclusion meaning desegregation it is increasingly defined by educational authorities to mean some kind of good teaching in general (Halinen & Järvinen, 2008; Special Education Committee, 2007).

Blom, H., Laukkanen, R. Lindström, A., Saresma, U. & Virtanen, P., 1996. Erityisopetuksen tila. [The status of special education] Helsinki: National Board of Education.

Conrad, P. & Schneider, J. W. (1980/1992). Deviance and Medicalization. From Badness to Sickness. Expanded Edition. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Emerson, E., Hatton, C., Bauer, I., Bjorgvinsdottir, S., Brak, W., Firkovska-Mankiewicz, A., Haroardottir, H., Kavaliunaite, A., Kebbon, L., Kristofferson, E., Saloviita, T., Schippers, H., Timmons, B., Timcev, L., Tossebro, J., Wiit, U. (1996). Patterns of Institutionalisation in 15 European Countries. European Journal on Mental Disability, 3, 29-32.

Halinen, I. & Järvinen, R. (2008). Towards inclusive education: the case of Finland. Prospects, 38, 77-97.

Heuru, K. (2000). Kunnan päätösvallan siirtyminen. [The shift of political power in local municipalitites] Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto.

Kivirauma, J. (1989). Erityisopetus ja suomalainen oppivelvollisuuskoulu vuosina 1921-1985. Turun Yliopiston julkaisuja, C: 74. Turku: Turun Yliopisto.

Meijer, J.W. (Ed.) (1999). Financing of special needs education: a seventeen country study of the relation between financing of special needs education and integration. European Agency for Development in Special needs Education: Danmark: Middelfart.

Meskus, M. (2003). Eugenics and the new genetics as technologies of governing reproduction: the Finnish case. Vital politics: Health, Medicine and Bioeconomics into the 21st Century. London School of Economics, 5.-7.9.2003.

Moberg, S., Hautamäki, J., Kivirauma, J., Lahtinen, U., Savolainen, H. & Vehmas, S. (2009). Erityispedagogiikan perusteet. [Basics of special education] Helsinki: WSOY.

European Agency for Development in Special needs Education (2003). Special education across Europe in 2003. Trends in provision in 18 European countries. www.european-agency.org (read 16.5.2006).

Memo (2006). Memorandum of the school authorities of nine large towns (Unpublished).

OAJ (Teachers´Union) (1990). Opetuksen integraatio. [Integration of education] 21.11.1989. Helsinki: OAJ.

Rehabilitation committee (1966). Report of the rehabilitation committee. [in Finnish] A 8. Helsinki.

Special Education Committee (2007). Special education strategy. [in Finnish] Reports of the Ministry of Education, 47.

Statistics Finland (1981). Erityisopetusta saaneet oppilaat lukuvuonna 1979/80. KO 1981:7 Helsinki: Statistics Finland.

Statistics Finland (1989). Erityisopetus 1987/88. Koulutus ja tutkimus 1989: 16. Helsinki: Statistics Finland.

Statistics Finland (1999-2009). Education. Helsinki: Statistics Finland.

Statistics Finland (2009). Yhä useampi peruskoululainen on erityisopetuksessa [Still more students in comprehensive schools attending special education]. Retrieved April 28, 2009 from: http://www.stat.fi/til/erop/2007/erop_2007_2008-06-10_tau_008.html

Unesco (1994) The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality. Salamanca, Spain 7-10. June 1994.

United Nations (1993). Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities. Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly at its 48th session on 20 December 1993 (resolution 48/96).

United Nations (2006). Convention on the rights of people with disabilities. <http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/index.html> (read 14.12.2006)

Quelle:

Timo Saloviita: Inclusive Education in Finland: A thwarted development

Erschienen in: Zeitschrift für Inklusion, Ausgabe 01/2009

bidok - Volltextbibliothek: Wiederveröffentlichung im Internet

Stand: 12.04.2010